As the head coach of the Cleveland Browns in 1995, Bill Belichick was facing a unique dilemma. To the casual observer, Belichick’s run in Cleveland up to that point had been a rousing success. He had resurrected the once proud franchise from cellar dwellers to one of the best records in the league at 14-5 and comprised a coaching staff featuring a number of future NFL head coaches, including his up and coming defensive coordinator Nick Saban. The Browns also boasted one of the best defenses in the league, giving up the 5th fewest points in the history of the NFL. There was one problem-Belichick’s squad could not figure out how to beat the Pittsburgh Steelers, falling to them both times in the regular season and again in the playoffs. The Browns in particular struggled to provide adequate answers to the methodological attack the Steelers pro spread offense levied on their defensive structure. If they rolled to 1 high and played cover 3 with an 8 man front to stop the run, Steeler quarterback Neil O’Donnell would pick them apart with seam vertical throws-the primary weakness of spot drop cover 3. Alleviating this issue with man coverage wasn’t much of an option for the Browns, who lacked the personnel to match up with the Steelers skill positions. When they went to 2 high safeties to take away the seams and 4 vertical concepts, the Steelers would simply march the ball down the field with their run game against a light box. Belichick and Saban needed an answer divergent from traditional defensive theory, and what the two arguably greatest coaches in the history of the sport came up with was pattern match coverage-a tactic that would fundamentally change the way football was played.

Pattern matching is a strategy that combines zone and man coverage to theoretically get the best of both worlds. The general principle of Saban and Belichick’s invention was that a defender would initially play zone coverage, but then play man to man on any receiver that came through his zone. Conceptually, this allowed the defense to reap the primary benefit of man coverage-playing tight to receivers, along with the primary benefit of zone coverage-leverage. In pattern matching, defenders pick up receivers after the route distribution, which in essence becomes a safer form of man coverage. Saban and Belichick began designing match rules and carefully calculated leverage points within their coverage structure to remedy the obvious weak spots of cover 3-the flats and the seams. In what they referred to as Rip/Liz Match, the alley defenders would now carry the vertical of #2 to take away seam throws, while also moving their alignment to outside of #2 to help funnel him to the free safety and eliminate the flat routes. With the alley or curl defenders now carrying the seams, the defense could also maintain their run-fit integrity with an overhang to each side and keep a deep post safety behind them. What the Browns’ defensive architects had done was formulate the blueprint for stifling a spread passing attack while simultaneously stopping the run-a dilemma now more prevalent than ever in today’s game.

Belichick and Saban would eventually go their separate ways and continued to expand pattern match concepts into their defenses over the years. Saban in particular integrated pattern match principles into his split field coverages, coining his man match 2 high family of coverages as cover 7. Cover 7 has long been a primary piece of Saban’s strategy in defending modern spread offenses and is an umbrella term for his man match quarters coverages. It is modular by design-meaning that various aspects of coverages that fall into the cover 7 family can be mixed and matched in order to afford the defense the best possible answer to specific issues the offense presents. The inherent flexibility of cover 7 allows different coverages to be played to each side of the field completely independent of one another. This is by no means unique to Saban (Gary Patterson did this for years at TCU), but is a perfect encapsulation of what lies at the core of Saban’s defensive philosophy-always having a specific answer for whatever the offense does, regardless of however seemingly complex that answer might be. As Michael Lombardi, who worked with Saban on the Browns staff, describes in his book Education of a Coach:

When Saban ran our defense in Cleveland, he wanted to be in the perfect defense for each play. The thought of giving up 5 yards drove him as crazy as giving up 50. His impossible dream manifested in countless checks and adjustments before the snap of the ball. Decades later, you can still watch an Alabama game and see all the defenders looking toward the sideline for his last second adjustments.

At its foundation, cover 7 is about giving a numbers advantage to the defense and bracketing receivers. Cover 7’s man match rules put defenders in the position of playing man coverage with leverage, which often forces tight throwing windows for the quarterback. As discussed previously, in zone match defenders will initially drop to their zone and then play man once the routes are distributed and a receiver comes into their zone. In man match, a defender will play man coverage on a receiver until he does something that by rule tells that defender to then go play man on somebody else. This in theory allows the defense to play tight (pseudo) man coverage out of a 2 high structure with specific rules to challenge common horizontal and vertical passing concepts from the offense.

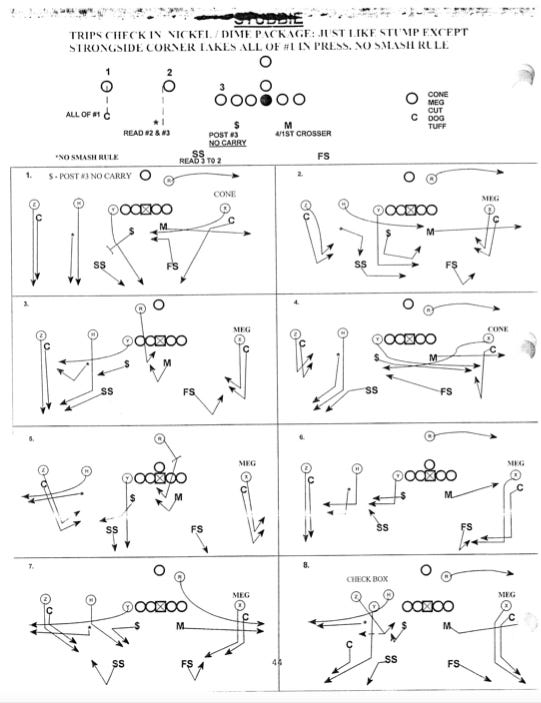

In Saban’s cover 7, the automatic check to trips is called “stubbie”. The first question defenses must answer when designing their trips coverages is how to stop 4 verticals and specifically who is going to defend #3 vertical. This especially becomes an issue with 1 high coverage categories, particularly cover 3. If the defense spins down strong, they can flood the frontside, but there is potential for a major mismatch with a linebacker carrying #3 vertical. This issue was prominently played out in the national championship game a few years ago, when an Ohio State inside linebacker was tasked with covering Heisman winner Devonte Smith up the seam. The boundary safety was rotating to cover the deep middle portion of the field, leaving him unable to help his outmatched linebacker with receivers running vertical up both hashes:

This is of course the same exact problem Saban and Belichick were facing in the 90s and why country cover 3 is an easily exploited plan versus modern spread offenses. Spinning the boundary safety down weak is also an option for cover 3 teams against trips so that the safety can cover the back out of the backfield instead of a linebacker, but the defense is still vulnerable to a 4 verticals concept with the weak hook player responsible for carrying #3 vertical:

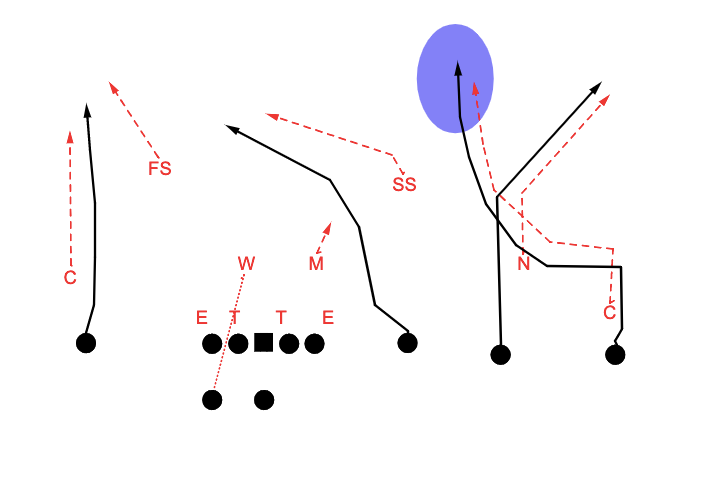

2 high match quarters coverages vs trips remedy the glaring weakness of cover 3 by having built in answers for providing the mike help on a vertical route by the #3 receiver. One popular way to do this is by playing “poach” or “solo” coverage, where the weak safety takes #3 if he goes vertical. The mike and weak safety bracket #3, while the corner, sam, and field safety play either quarters or 2 read over the #1 and #2 receivers:

The weakness of poach coverage is of course the backside, with the boundary corner isolated on the X and the will linebacker covering the back. Unless the defense has a dominant corner, this coverage can be easily exploited. The weak safety can only help the boundary corner if #3 does not go vertical. Route concepts like the one Oklahoma ran below during the Lincoln Riley era take advantage of these rules (this is from Noah Riley’s excellent Breaking Down the 2018 Oklahoma Offense book). Here TCU is playing solo coverage. The boundary corner is matched up one on one with a vertical by the X. The weak safety must take #3 vertical but is out leveraged by the corner route, while a linebacker has to take the back vertical up the seam:

Another popular poach/solo beater is the old air raid staple Y Cross out of trips and tagging the X on a post. The free safety has to take the cross, leaving the boundary corner isolated on the deep post:

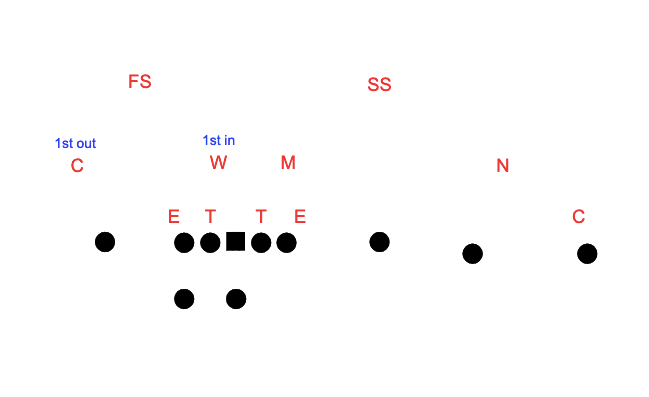

Saban’s split safety cover 7 allows the weak safety to help the boundary corner by keeping him on the weak side (although he can work to the strong side based on certain rules, more on that later). The underlying principle of the concept is to have a plus one numbers advantage to each side-4 over 3 to the strong side and 3 over 2 to the weak side:

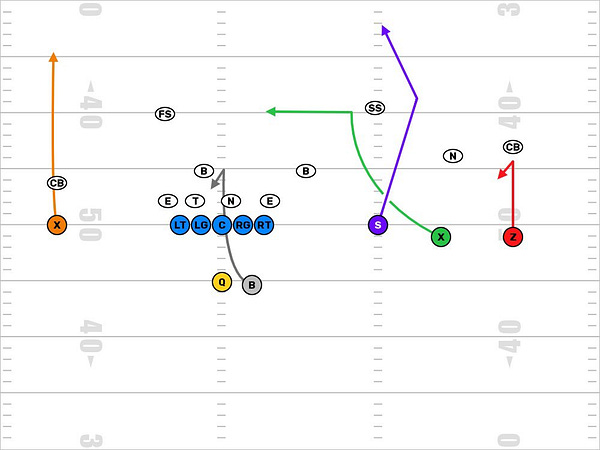

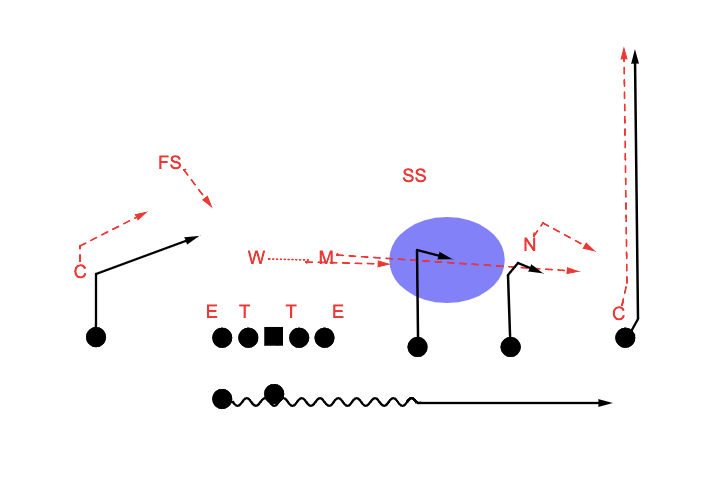

How exactly that numbers advantage is allotted to each side is based on the specific game plan for each week, and there are a variety of options within the cover 7 family at Saban’s disposal to take away what the offense does best. Stubbie falls under the cover 7 umbrella and is the most common coverage Saban runs to trips. It is best used when the offense is running a lot of quick outs or bubble screens by #3 and high/low concepts with the slot receivers-both extremely common tactics by today’s spread offenses. The philosophy behind stubbie is built on the law of averages, which says that most offenses rarely throw to the #1 receiver to the trips side. Based on this line of thought, the defense will only use one defender to cover the #1 receiver-the field corner. The corner will use a press man technique with inside leverage to try and force the receiver outside (a further throw for the quarterback). The mike, nickel (referred to as the money and star in Saban’s terminology), and strong safety will form a pattern matching triangle over the slot receivers and play a cloud (2 read) concept. The nickel will essentially operate just like a 2 read corner-he will play outside technique of #2 and is responsible for all of #2 vertical, but if #3 runs an out he will trap the out. The outside leverage of the nickel is what makes stubbie so advantageous versus bubble screens and quick outs by #3. The strong safety is responsible for #3 vertical, but if #3 runs in or out he will top #2 vertical. So for example, if the #3 runs an out and #2 is vertical, the nickel will jump the out, while the strong safety will take #2 vertical:

The structure of the coverage ensures that the mike will not have to carry #3 vertical. Instead, he will have the first inside route out of #2 and #3 and execute a post technique, which basically means his assignment is to not let anybody cross underneath him. Along with not having to worry about a mismatch covering #3 vertical, one of the primary advantages of stubbie is that with the nickel playing trap, the mike doesn’t have to push with the out of #3. This banjo-esque assortment frees the mike up to stay closer to the box where he can quickly get to his run fit and is less susceptible to RPOs.

Stump is essentially the exact same coverage as stubbie, but with a rule built in to take away the smash concept. The corner will get in an off alignment with inside leverage and play the #1 receiver man to man unless he runs a route under 5 yds, in which case the corner would make an under call, alerting the nickel that he now has to take the #1. The corner will sink and help with the vertical of #2.

As former Alabama assistant Jeremy Pruitt explained at a coaching clinic, the inside leverage of the corner in stump puts him in a better position to defend the mills concept, which teams will often run when they know the strong safety is playing quarters rules and will nail down on a curl or dig from the #3 receiver:

If the corner bails with outside leverage this play is a quarters killer, as recently evidenced here:

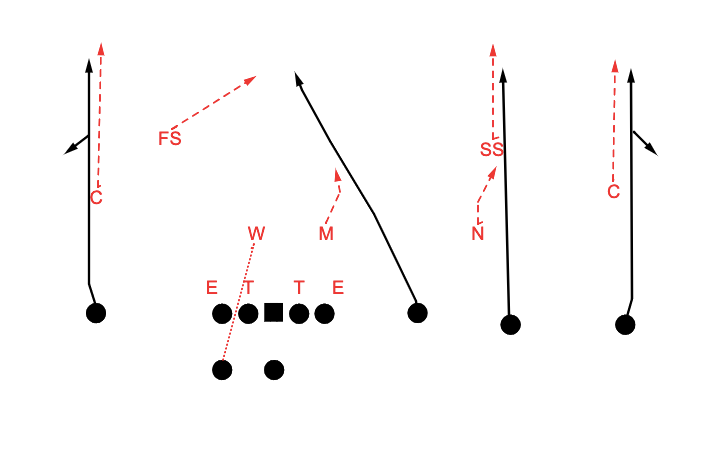

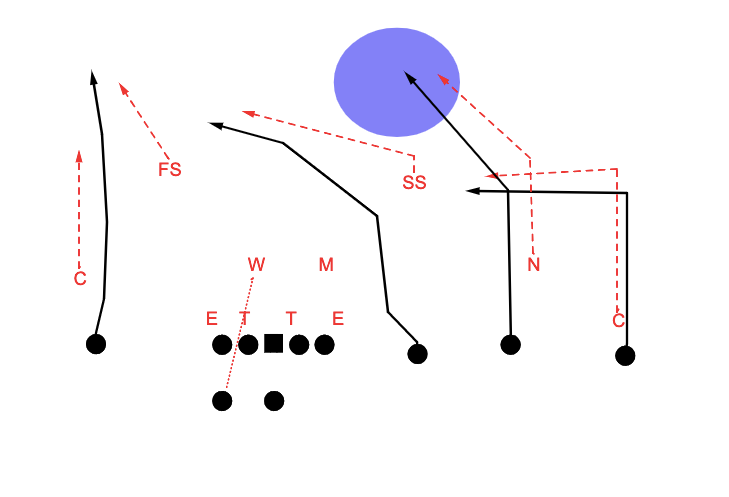

There are a variety of coverages that can be played to the backside of stump or stubbie, but the most common one is called cone, where the free safety and corner bracket the #1 receiver. The free safety plays inside and the corner plays outside. If the X releases inside, the free safety will take him and the corner will zone off. If he releases outside (which because of the corner’s alignment should rarely happen) the corner will take him and the free safety will now work to the strong side. The will linebacker is locked on the back:

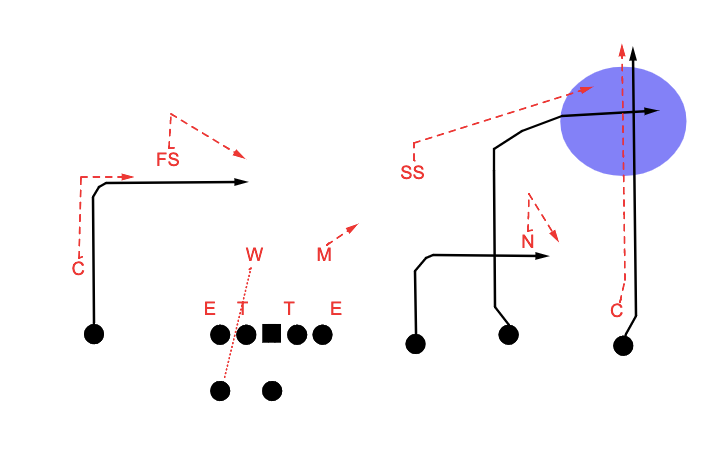

Against a tight split by the X receiver, the defense will typically check to a connie call, which is basically a man match version of cover 2, where the corner will take the first outside route and the will linebacker will take the first inside route. These rules negate pick/rub concepts that are commonly run out of a condensed split look by the X. The free safety will help with any deep routes to the weak side, but will work front side if both routes are short:

Offensively, it is an imperative to understand that every coverage has its own unique strengths and weaknesses and that no coverage is designed to stop everything. A defense must pick their poison when it comes to pass coverage. Stubbie and stump allow the defense to double someone on both sides of the ball in what should be a tight, constricted coverage look for the quarterback. However, the primary weakness of the coverage is the nickel being forced to carry the #2 vertical against certain route distributions. This deficiency is the reason why the first answer for most offenses seeing stubbie and stump is 4 verticals. Whether it is stump or stubbie, if the offense runs all 4 receivers vertical the nickel now has to defend #2 vertical up the seam from outside leverage with no help. Backside, if the defense is running cone, it is important that the X receiver takes an inside release to ensure the free safety takes him vertical:

As mentioned earlier, one of the potential weaknesses of stubbie coverage is the field corner’s one on one matchup with the #1 receiver. With the NFL caliber talent regularly coming through Tuscaloosa, this is a risk Alabama is more than willing to take and is one of the reasons Saban prefers stubbie over stump (he also feels like his corners are more comfortable playing press man because that is what they do most of the time). Most places may not feel quite as confident with the field corner being left on an island, and this is certainly an area the offense can look to exploit. If the quarterback has the arm strength, there are numerous ways to win outside with a mismatch, whether that be with a vertical, post, curl, etc. In what ends up being vertical spacing, the concept below splits the nickel and strong safety and can help break the #1 receiver open up the seam vs stubbie:

This would not be as effective versus stump because the corner would make an under call and then fall off to help defend the corner route, while the nickel’s rule would tell him to switch off to cover #1.

The positioning of the nickel outside of #2 opens up a number of possibilities for the offense to attack and use that leverage against him. One of the most popular ways to do this is with the levels concept, where the #3 receiver runs a dig, and the #2 and #1 receivers run “fin” or 5 yard in routes. The dig should hold the strong safety as he has to respect the vertical threat of #3, and the fin route by #2 becomes extremely difficult for the nickel to defend with outside leverage. The mike is also placed in a high/low stretch:

Similarly, the “dusty” concept puts the #1 and #2 receivers on fin routes and the #3 on a corner.. Whether it be stubbie or stump, the 5 yard in should be an easy completion for the quarterback as long as he can fit the ball in before the mike can get there:

As Seth Galina pointed out on twitter, Chad Morris used an interesting tag off of the “dusty” concept as a stubbie beater a few years back during his time at SMU. The #2 receiver initially runs a 5 yard in route before bursting vertically up the seam. The strong safety takes #3 on the corner route, while the nickel/sam zones off to help with the corner. This leaves the mike in an awkward position thinking initially he is going to be posting the in route of the new #3, but then being forced to run with him vertical:

This variation of Y cross from Lincoln Riley also takes advantage of the nickel’s outside leverage. The strong safety is forced to run with #3 vertical, creating a huge throwing window for the curl:

The arches concept (made famous by Mike Martz during his time in St Louis with the Rams) takes advantage of the rules for underneath defenders in stubbie and stump. Also a favorite of Steve Spurrier against Saban defenses, the #3 receiver runs a drag or shallow route to occupy the mike, while the #2 receiver runs an angle or slant route, widening at first to keep the nickel in his outside position before breaking back inside to the open void:

Teams will also have the #2 receiver run the shallow and the #3 run the angle/slant route, which by alignment should help even more with ensuring an inside leverage position on the nickel:

As mentioned previously, one of the primary weaknesses of stubbie in particular is the nickel being forced to carry the #2 receiver vertical against certain route distributions. One way the offense can exploit this vulnerability is with a scissors concept, where the inside receivers run a post/corner combination. The nickel should have difficulty covering the post from his outside alignment. The concept also has the effect of placing a high/low stretch on the strong safety:

This route combination has the capability to be even more deadly against stump because of the smash/under call the corner will make when he sees #1 run his route under 5 yards. The nickel will now take #1 and the corner will have to try and defend the post route from outside with no help from the strong safety, who is occupied by the corner route:

The strong safety and corner could in theory pass those routes off and still be in a good position, especially if this is something they’ve seen on film and repped during the week. One way to prevent this is to run the mills concept covered earlier and put #3 on a dig instead of a corner route:

A similar idea is to run Y cross with #2 on a post and #1 on a dig, which is basically the mills concept inverted and commonly referred to as “dagger”. Whether it be stump or stubbie, the nickel will be stuck defending the post with the strong safety eaten up by the cross route:

When the defense is in stubbie, running the classic mills concept with #1 on the post takes advantage of the space behind the strong safety when he nails down on the dig route:

As demonstrated earlier, this play is one of the primary reasons that the corner gets inside leverage on his bail technique after an under call when running stump. Another creative way of running mills and using the defenses’ rules against them is switching the #2 and #3 wide receivers on their release path. From @_MoveTheChains_ :

The sail concept with the #2 running the sail can also be a solid way to attack stump or stubbie. The nickel will trap the out by #3, while the strong safety (who is initially lined head up on a detached #3) must now try to defend the sail route from an inside position:

A classic stubbie/stump beater out of trips is stick, and out of all these concepts is probably the easiest completion for the quarterback. It takes advantage of the bubble between the mike and nickel. The out by #2 forces the nickel to expand, creating space for the short out/stick in the open void. The #1 receiver must take an outside release:

What puts even more stress on stubbie/stump coverage when running this concept is putting the tailback on fast motion to the strongside. This distorts the under coverage, and by rule forces the mike to take the back (the new #3) and the will linebacker to become the new post/wall defender, creating even more space/leverage for the stick:

Finally, a cover 7 beater backside that was popularized by the Patriots would be out of a condensed split by the X to force a connie call. As discussed previously, connie is basically man match cover 2 and is designed to help protect the will linebacker from getting picked by the X while trying to cover the back out. The corner is aligned outside leverage, 4-5 yards off and slow bails to help him read the release of the receiver. This beater uses the defenses’ rules against them and from a conceptual standpoint is similar to arches. The X will run a shallow to occupy the will, while the back runs a follow or angle route that attacks the outside leverage of the corner before breaking back inside:

It is important to note that if an offensive coordinator is frequently using these concepts in a game, Saban and his disciples would not continue running stubbie or stump and instead utilize one of the other myriad of coverages at their disposal. If they are seeing a heavy dose of stubbie and stump beaters, they would switch to something like clip coverage, as Jeremy Pruit emphasized at a clinic, “All these routes that beat stubbie and stump are not any good versus clip.” Clip is essentially a man match version of cover 2 that is better designed to handle 4 verticals and in breaking route concepts like levels. And therein lies the beauty of Saban’s system-that amidst the emphatic focus on volume and meticulous attention to detail there is always a pinpoint answer available for the defense to counter the offensive attack. Offensive play callers are in for the ultimate chess match when facing a Saban system defense, and the match principles that Belichick and Saban popularized years ago remain at the forefront of strategy for combating modern day offenses.

Resources

Breaking Down the 2018 Oklahoma Offense by Noah Riley

How to Beat Every Coverage Course by JT O’Sullivan

Make Defense Great Again Podcast

Deep Dive on Defense with Dante Bartee

Blood, Sweat, and Chalk by Tim Layden

The Education of a Coach by David Halberstam

Gridiron Genius by Michael Lombardi

The Essential Smart Football by Chris Brown

Evolution of the Game by Frank Francisco

After the Boom: A new way for NFL defenses to attack sophisticated passing schemes

Split Safety Coverages Clinic Jeremy Pruitt

Karl Scott Alabama Match Quarters Clinic

Understanding the Basics of Cover 7 Ted Nguyen

Excellent break down Coach! Thank you sharing this.