How Will Stein Teaches the Spacing Concept

Will Stein’s inaugural season as Oregon’s offensive coordinator was ripe with success. The Ducks finished the year as the 2nd ranked total offense (behind only LSU) and the top ranked passing attack in the country, with veteran quarterback Bo Nix throwing for 4,508 yds, 45 touchdowns, and just 3 interceptions. What is arguably most impressive about Stein’s Pac 12 debut is the efficiency in which the 34 year old play caller’s scheme operates. Nix finished the year with a 77.4 completion percentage (1st nationally) and the offensive line gave up only 5 sacks (1st nationally) all season. Stein’s offense at UTSA in 2022 produced similarly impressive results at the QB position, where Frank Harris threw for 4,063 yds and 32 TDs with a 70% completion percentage.

One of the foundational plays of Stein’s passing offense going back to his first year calling plays at Lake Travis High School is the spacing concept. The objective of spacing is, as the name entails, to space receivers out evenly across the field to gain a numbers advantage against underneath coverage. It was a staple of Bill Walsh’s 49ers teams, where they would isolate Jerry Rice as the lone receiver out of a 3x1 formation and have him run a slant. The only way to stop Rice in his heyday was to double him, in which case the defense would be left in a 3 on 2 situation to the 3 receiver side. It has been an essential element of the Walsh derivative offenses ever since, with Sean Payton even being quoted as saying “Spacing is the second read to everything.”

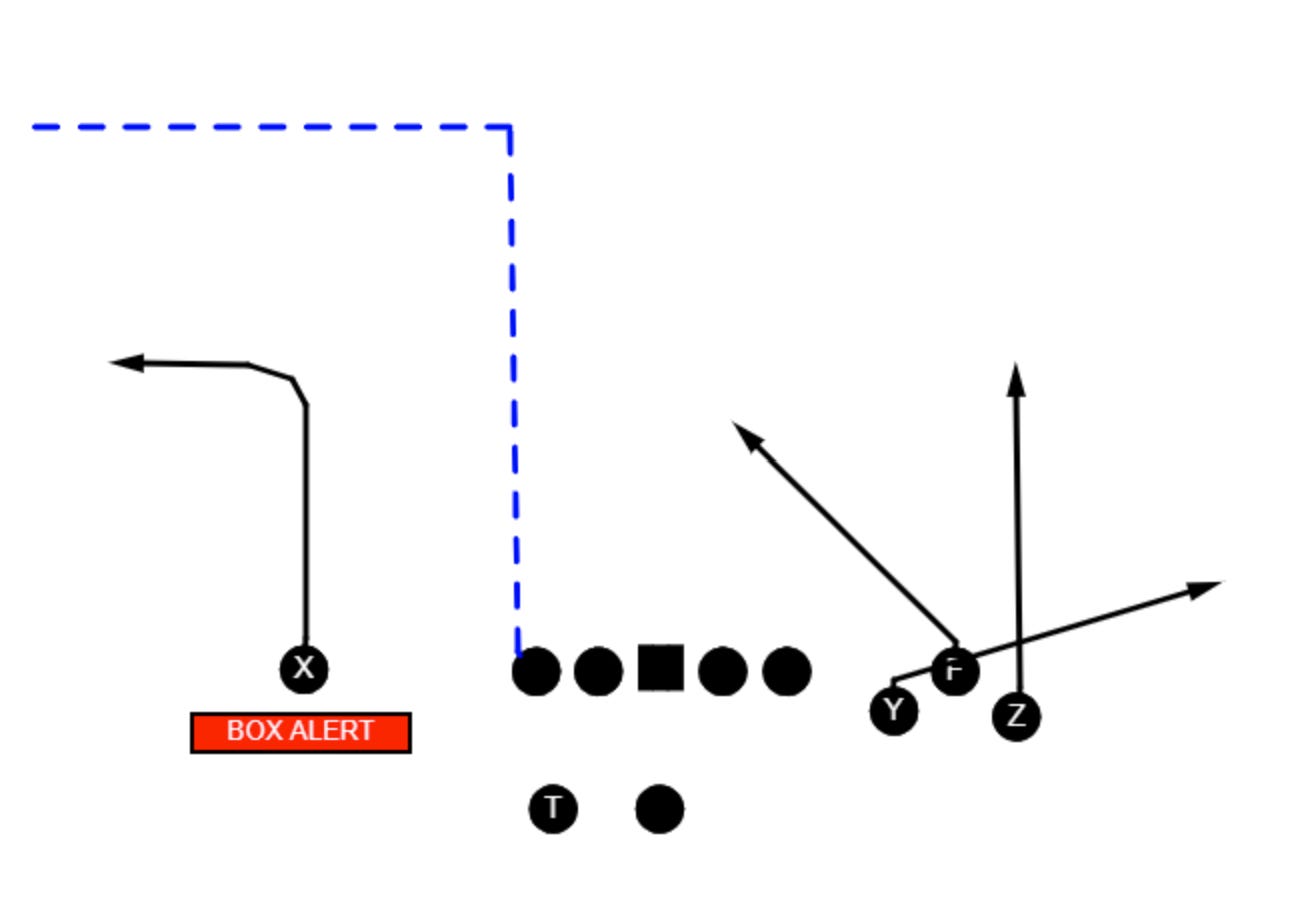

Stein begins teaching quarterbacks his version of spacing as a full field read where they have a one on one to the boundary, and a foundational read (spacing) to the 3 receiver side. If they get one on one to the single, their thought process is that they are going to throw that route every time. If they don’t get one on one or if the single side receiver just doesn’t win his match-up and get open, they will then work the spacing side. The single receiver can run a variety of different routes based on the game plan-a hitch or a quick out is good vs an off corner, while a fade is best when seeing press. They will also at times involve the back and run 2 man combos to that side. The method Stein uses to help his quarterbacks determine if the defense has allotted an extra defender to help the corner is by using a “box alert”:

If the X is left in a 1 on 1 situation in the “box”, the quarterback is coached to work that match-up every time. For example, if the boundary safety rotates to the middle of the field in some sort of strong rolled coverage look, using his box alert, the QB knows to work to the single because he is getting a 1 on 1 look:

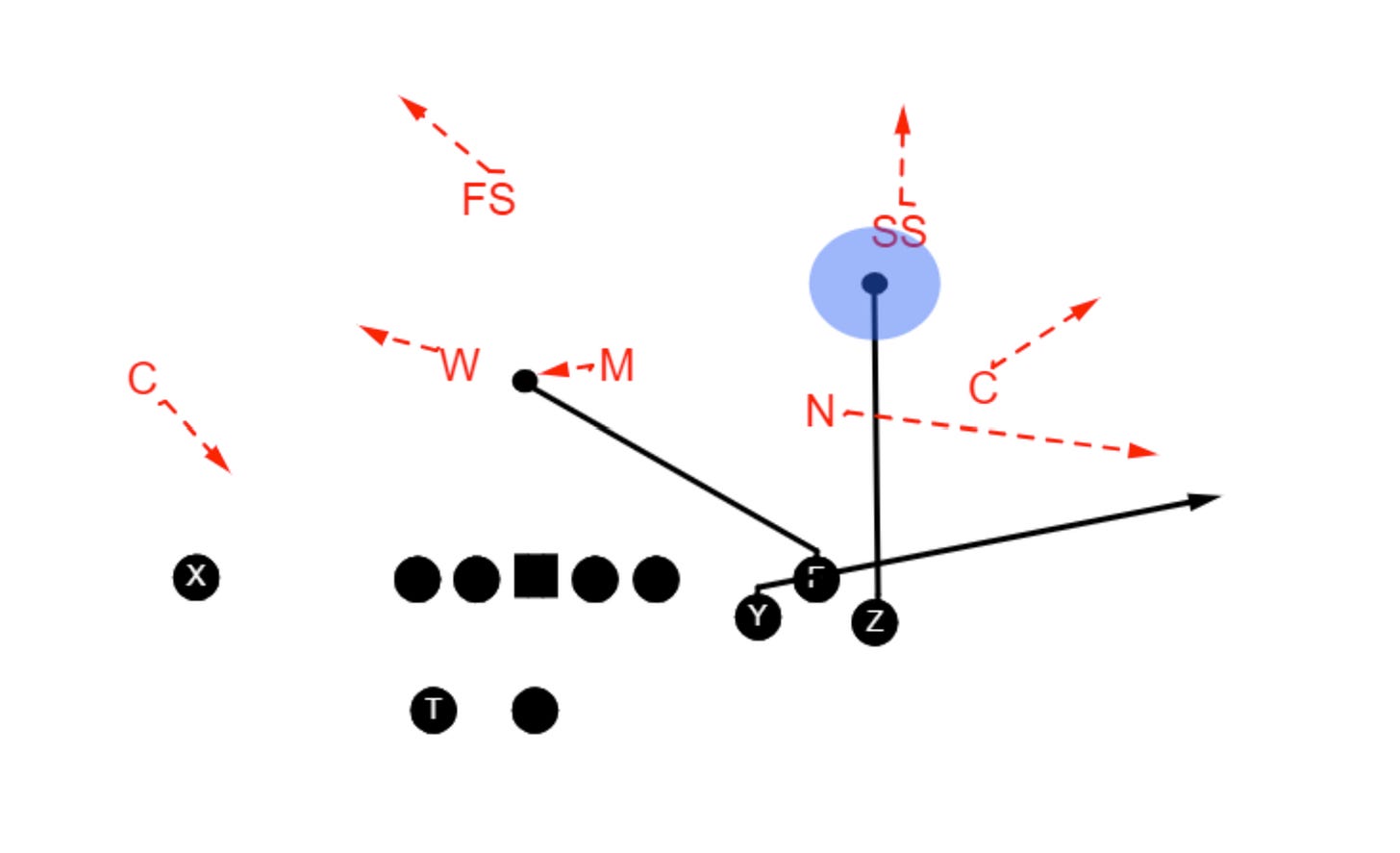

However, if the defense presents a 2 on 1 look, the quarterback will now work the spacing side of the play. There are a number of different defensive tactics that result in a numbers advantage over the X receiver. An example would be a rolled-up corner in cloud coverage with a safety over the top:

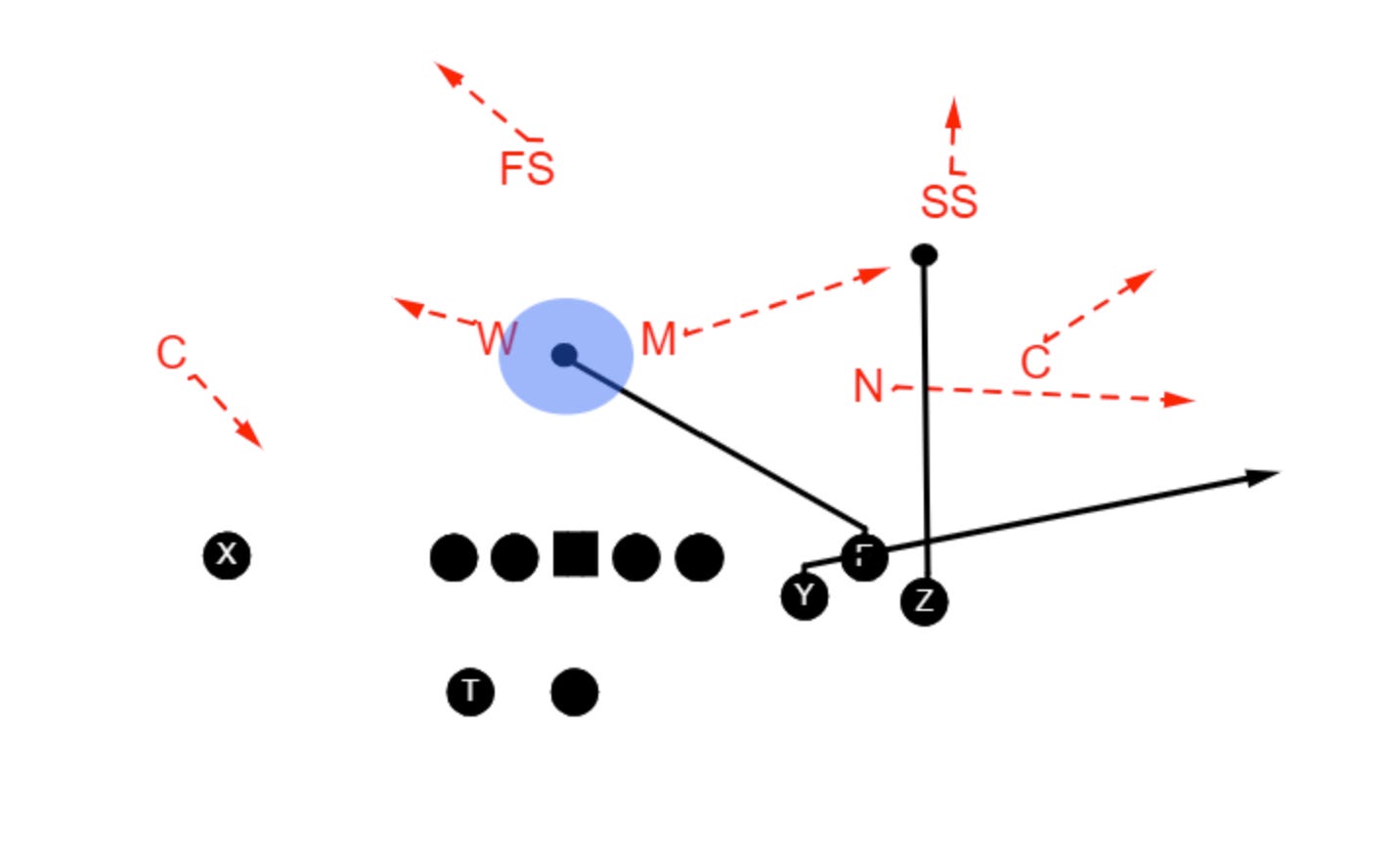

Another example would be sky coverage where the boundary safety rotates down to cover the flat and the corner takes deep third:

Ultimately if the defense is in a plus one situation to the single, or if there is any doubt in deciphering defensive intention, the quarterback will start on the spacing concept side and look outside in. Typically Stein likes to use a bunch formation to the field when running this play, with the receiver at the point of the bunch running the over the ball route at 6 yards deep. He will punch and pivot at the top of his route, show hat and hands, catch the ball on whatever the shoulder the QB gives it to him, then drop step and get vertical. The #3 receiver will run an arrow route, with an aiming point 2-3 yards deep on the sideline. The #1 receiver will run what they call a spacing hitch at 6 yards deep. The objective of spacing is to create a 3 on 2 situation in underneath coverage. It is an ideal play to run against teams deploying a soft zone look. The OTB and hitch route place the hook defender in a horizontal stretch, while the hitch and the arrow put the flat defender in a similar conundrum:

The rhythm of the play is calibrated so that if the quarterback knows he is working the spacing side because of a 2 on 1 box alert, he will look outside in, with his progression being arrow, hitch, over the ball. Stein coaches his quarterbacks to read the play outside in because in his words, “We don’t want to ever throw late to the flat-that is the cardinal sin of playing quarterback. So if you don’t want to throw late to the flat-start with your eyes to the flat.” What typically happens is the QB stares down the arrow and the flat defender jumps it, which opens up the spacing hitch in the seam:

If for some reason the hook defender gets involved in covering the hitch, the over the ball route should be wide open:

If the QB gets a pre-snap 1 on 1 box alert, he will as previously mentioned approach the play thinking he is going to throw to the single. However, if the single side receiver for whatever reason doesn’t get open, the QB will reset and work the spacing side with an inside out progression-now looking at the over the ball route first, the seam hitch second, and the arrow route third. The beauty of the play is that the two separate rhythms-with quick game on one side and spacing on the other-in a sense provide the quarterback with two leases on life in the passing game. Philosophically, spacing can best be summarized by the old adage of “taking what the defense gives us.” The defense’s decision on how to cover the X receiver should predicate where the offense goes with the ball. If they over rotate or use brackets to help the single side corner, the offense should be able to out number the secondary with 3 receivers spaced out laterally against 2 underneath defenders. The other aspect of the play that makes it so reliable and efficient is that the quarterback has stationary targets on the spacing side to throw to instead of receivers moving across the field.

In this first example from Stein’s time at UTSA, they are running a 2 man combo to the boundary they call “bite” which is essentially snag. The boundary safety is working off the hash and the corner is playing a flat footed, outside leverage technique at 5 yards deep, indicating to the quarterback some sort of cloud coverage and therefore a 2 on 1 box look. The quarterback knows pre-snap he is working the spacing side, so he uses an outside-in progression. The corner jumps the flat route, so the QB throws the seam hitch:

Later in the game again on 3rd and medium, UTSA runs the same play. The defense is now in a cover 3 look, and the “bite” concept puts the flat defender in a horizontal stretch. He drops with the snag route, so the QB dumps it off to the back on the swing:

On 3rd and 7 in the 4th quarter, UTSA again comes back to spacing, but this time with formation into the boundary (FIB), which forces the defense into a difficult position. If the coverage is rotated 1 high into the boundary to the strength of the formation, this leaves the field corner in a 1 on 1 situation with no safety help. If the defense stays 2 high to eliminate the 1 on 1, the offense should have a numbers advantage to the boundary. In this case, the defense keeps a 2 on 1 look to the field to help the corner vs the tagged double move-a slant and go by the X. The QB makes a pre-snap decision to work the spacing side, and again hits the seam hitch:

This past season at Oregon, Stein occasionally utilized the spacing concept, mostly in third and short to medium situations. Here against Texas Tech, Oregon is in FIB with the single side receiver to the field running a slant. Quarterback Bo Nix sees a 1 on 1 box look and throws the slant for a completion and first down conversion:

In this last example against Portland State, Oregon again runs a formation into the boundary, then motions the back out to the field to run their “bite” concept. Portland State is in a cover 4 look, and the flat defender initially widens with the motion while the corner stays tight to the snag route. Nix’s eyes first start to the bite side, then to spacing looking inside-out, then back to the field late where he throws the swing open in the flat. He probably could have thrown the over the ball route, as the hook defender vertically dropped a few steps before closing in to cover:

Resources

https://compusportsradio.com/coachscornervol24.asp

r4footballsystem.com

glazierdrive.com-will stein 3 and 4 man spacing

Fast and Furious: Butch Jones and the Tennessee Volunteers Offense