How Zach Kittley Used the Snag Concept at Western Kentucky

By Wesley Ross

Zach Kittley’s electric offense this past season at Western Kentucky put the normally below-the-radar Hilltoppers program onto the national scene. Led by transfers Bailey Zappe and Jerreth Sterns, WKU finished the season averaging 44 points and 536 yards per game, second behind only Ohio State in total offense. Zappe, who followed Kittley from Houston Baptist, put up video game-like numbers at quarterback, setting the NCAA all-time single season record for both touchdowns (62) and passing yards (5,967). Sterns, who was also a senior graduate transfer from Houston Baptist, led the nation in receptions (150), TD receptions (17), and receiving yards (1,902). The success of the offense helped Kittley land the offensive coordinator role at Texas Tech under new head coach Joey McGuire.

Kittley’s pass heavy offensive philosophy is firmly rooted in the air raid, stemming from his time as a student assistant and GA under Kliff Kingsbury. Familiar staples of the system originally made famous by Hal Mumme and Mike Leach were omnipresent in WKU’s offense, particularly a heavy dose of 4 verticals and Y stick (although they preferred the Y stick/slot fade variation). Another primary passing play the Hilltoppers used throughout their record breaking 2021 season was the snag concept.

Snag (otherwise known as “8” or “Y corner” in the air raid) features a corner, spot (also referred to as a snag or lazy slant), and flat route that together place a triangular stretch on the defense:

Theoretically, against zone coverage the corner and flat route should place a vertical stretch on the cornerback, while the spot and the flat should horizontally stretch the flat defender. Against 2 high zone structures, whether it be cover 2 or cover 4, the vertical component of the play should play out as the primary feature, with the cornerback being forced to choose between the corner and the flat route. The read for the quarterback is simple-throw off of the cornerback’s movement and make him wrong. If he bails to cover the corner route, throw to the flat (cover 4 rules):

The exception to this would obviously be if the outside linebacker flies out fast enough to adequately cover the flat. In that case, the spot route runner should be open as he settles into the window between the flat and hook defender:

If the cornerback jumps the flat, throw to the corner (cover 2 rules):

Against cover 3, the cornerback should bail to his deep third and cancel out the corner, leaving the apexed flat defender in the precarious position of covering both the spot and the flat. The quarterback will now throw off of the flat defender’s movement:

If executed correctly, snag should be impossible to defend with zone coverage. However, the weakness of triangle concepts like snag are brought to bear when the defense responds by over rotating to the triangle side. For example, within two high zone structures, the defense can cheat the mike over to cover the spot. Now the defense has a numbers advantage to the snag side:

This is why the complimentary passing concept placed to the backside is so important-it must take advantage of this overreaction by the defense. Typically this would be double slants to fill the open void left by the Mike, or some sort of dig/pivot or levels concept designed to place a high/low stretch on the flat defender.

Snag’s versatility is also evidenced by its structural answers to defeating man coverage. The corner route is in and of itself an excellent man beater route, especially considering the potential mismatch with a linebacker or safety on an inside receiver. The spot route presents another man beater element to the play with the rub it places on the defender covering the flat route. This can be particularly tough on an inside linebacker, who must make his way through the corner and spot route runner in an effort to try and cover the back out in the flat.

Within the air raid system, snag (or Y corner) developed as the companion play to Y stick. Stick is a short, ball control passing concept that places a horizontal stretch on the flat defender:

Against a split coverage team, Mumme and Leach would ensure that stick was a prominent part of the game plan. When the strong safety would begin to cheat down in an effort to eliminate the stick concept (often in the red zone), Y corner was the obvious constraint play because it took advantage of the open void that was now left behind the cornerback:

As the safety came down, the Y would run a 4 step corner, giving a slight head fake to the Mike before cutting to an aiming point 1 yard inside the back pylon ( it is better to be too high on the corner route than too flat because it is easier to come back to the ball). As this was happening, the Z would run a lazy slant/snag route (he was coached to fake a fade against a rolled corner) and take the Y’s place on the stick. The Y and Z were essentially exchanging positions from where they were on the stick play. The tailback would cheat his alignment out and run a shoot with an aiming point 2-3 yards out of bounds. The quarterback’s progression was simply corner, shoot, spot. Some air raid coaches will teach their quarterback to note the depth of the cornerback pre-snap. If the cornerback is playing off, he will eliminate the corner route in his progression and have an easy read on the Sam, just like on stick. If the corner is playing down, the QB will now go through his progression with a potential mismatch on a corner route against a backer.

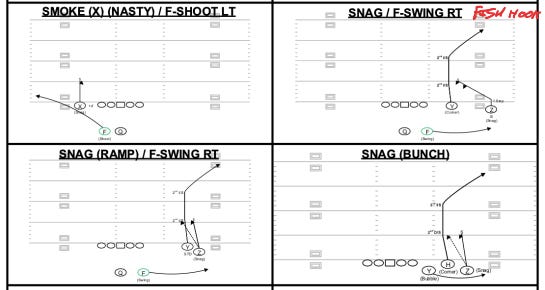

Kittley’s version of the play is similar but puts the #2 receiver on a deeper 10 yard corner. He most likely took this iteration of the play from his time learning under Kingsbury. Below are 3 different variations of the snag concept from the Cardinals 2019 playbook:

In the clip below, Western Kentucky runs snag in the red zone on a critical 4th down. The cornerback jumps the shoot, isolating Sterns on the corner route against an outmatched linebacker:

Against UTSA they put the back on tear motion, which allows Zappe to identify man coverage when the backer vacates the box to run with him. The #2 receiver does a good job of stemming and getting on the defender’s toes to break open on the corner:

Here against Marshall, they again put the back in tear motion before the snap. This can have the effect of making it an easier read for the quarterback because it puts the flat defender in a more immediate bind. In this case, the under coverage gets distorted as the flat defender expands with the pre-snap motion and jumps the swing, allowing the spot to settle in the open void between the flat and hook defenders:

The same play with the same result against Old Dominion:

Hitting the spot route in the red zone out of a compressed set, shared by @_MoveTheChains_:

WKU would usually pair snag with double slants on the backside. Here out of empty Zappe initially checks the snag side, then looks back side and hits the slant return. I have no way of knowing for sure without access to their playbook, but it is possible that this is kind of an option route, where their outside receiver is coached to work back toward the sideline if he doesn’t initially get the ball on the slant:

Backside slant touchdown throw on a redzone 4th down:

Again on 4th down, UTSA is in man free and Zappe works the vertical/out combo to the backside:

Here against Marshall, Zappe works a high/low combo on the backside flat defender:

Later on in the game they run snag and go, where the outside receiver basically fakes snag and then runs vertical. Typically this play is designed to defeat split safety coverage, whereby the safety widens to carry the corner from #2, leaving a void in the middle of the field. Here Marshall rolls to cover 3, and Zappe ends up throwing an incompletion trying to hit the snag and go up the seam:

Special thanks to @_MoveTheChains_ and @CoachT_Robinson for sharing their research with me on WKU’s offense.