Sid Gillman's Passing Game Theory and Johnny Manziel's Favorite Audible

In January 2014, Johnny Manziel was on top of the football world. The 2012 Hiesman winner had just capped off a legendary collegiate career with a comeback win over Duke in the Chick-fil-a Bowl and was looking to shirk his party-boy image in an effort to improve his draft stock. Selecting a quarterback early in the draft is always a risky investment for an NFL franchise, and Manziel needed to convince scouts that the high maintenance, wild-man reputation he had earned in college was something of the past. Part of the pre-draft process for Manziel was a 3 month stint training with private quarterback coach George Whitfield and his staff, which included former NFL quarterback Kevin O’Connell. O’Connell’s role was to improve Manziel’s football IQ by teaching him certain aspects of the game that he didn’t have to worry about in college-things like identifying the mike, calling protections, etc. Essentially, O’Connell’s job was to enhance the cerebral aspect of Manziel’s game so that when coaches and GMs began drilling him with Xs and Os questions at the combine, he could ace the interview.

In their first meeting, O’Connell opened up by explaining to Manziel what would be expected of him as an NFL quarterback, which began an interesting exchange detailing audibles and coverage beaters. From Bruce Feldman’s excellent book, The QB: The Making of Modern Quarterbacks:

Manziel was already in the exclusive Heisman fraternity, but O’Connell was hoping to help him into a different kind of fraternity. One with Peyton Manning, Brees, Brady, and a select few others who had the answers to the test before the ball ever reached their palms. ““What you’re seeing nowadays is,everybody in the NFL is going to this system where the quarterback has a package of plays that he can get to depending on what the defense is in,” O’Connel told Manziel. “You’re not just gonna call ‘four verts.’ The quarterback will check to it when he sees the appropriate look from the defense. Basically, nobody’s wasting plays anymore. And all of that is predicated on what you do watching tape and your preparation.”

Manziel had a similar story from his own days in College Station, jousting with Aggies defensive coordinator Mark Snyder, whose go-to defense was often “Tampa 2,” according to the QB. “If we had a run play, and they’re gonna crowd the box, I check,” Manziel said. “Then he checks. I didn’t even have to look over at him. I know what his go to check is. The first thing we’re going to is all-curls to high low with a hook over the middle replacing the MIK [linebacker] every time.”

O’Connell: Draw it up. Perfect segue. OK, everytime you go up to that board, I want you to act as if Bill O’Brien is sitting where I’m sitting. Presence. Voice. Hold that thing [the marker] like you’re holding the keys to the franchise.

Manzeil quickly ran through some A&M offensive staples. He explained a couple of details of “93,” which is “all-curls” run at 13 yards deep, pointing out the general idea behind the play: “He [pointing to a receiver] has this whole area from hash to hash to work. Obviously, MIK [middle linebacker] is gone. Replace.” With each bit of information Manziel offered, O’Connell peppered him with questions, asking for more specifics.

O’CONNELL: Where are the Z and X [receivers] alignments? Are they touching paint [the numbers on the field]?

MANZIEL: They’re on top of the numbers every time.

O’CONNELL: So top of the numbers, college, would be bottom of the numbers, pro. Perfect.

O’Connell wanted Manziel to get used to the altered geometry of the college game compared to the NFL due to the pro league’s narrower hash marks, which meant, for quarterbacks, landmarks and angles and typical dead spots against coverages were different.

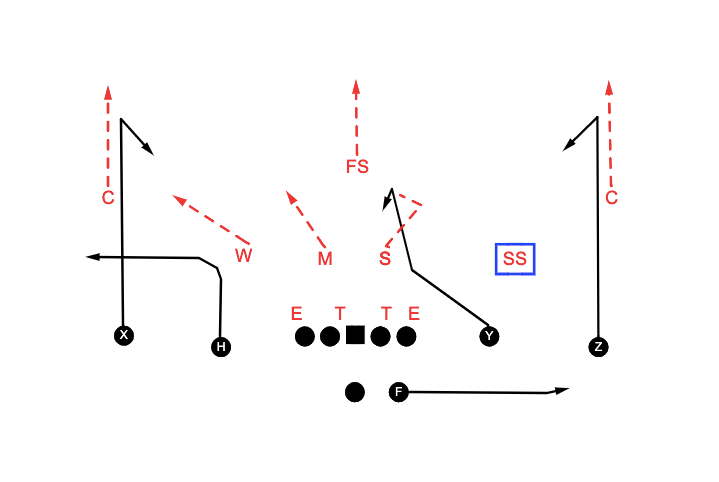

All curls or “93” as it is called in air raid terminology, is designed to place a horizontal stretch on the defense by positioning more receivers across the width of the field than the defense has the numbers to cover. It is perfectly designed to defeat cover 3, which distributes 4 underneath defenders against 5 eligible receivers. Andrew Coverdale, when explaining a similar curl/flat concept commonly referred to as “Hank” at a recent Nike Coach of the Year Clinic, likened it to a 5 on 4 fastbreak situation in basketball. In the diagram below, if you are the green dot at the top of the key, you will take the ball to the hoop as long as the defense will let you. If however, the defense decides to converge and stop you, you will then pass the ball to where the defense is not, whether that be to your teammate on the wing or in the corner:

Similarly, the all curl concept is an “inside out” play, meaning that the quarterback will first try to get the ball to the middle curl. If the defense reacts by squeezing and taking away this inside portion of the play, then the offense should now have a numbers advantage to the outside with the curl and flat route. For example, against cover 3, the defense must first stop the middle curl route with at least one of the hook/curl defenders, which prevents this defender from being able to get into the curl window. This is why many coaches will have the quarterback work curl/flat to the side of the hook defender that squeezes the middle curl. The alley defender is now left in a 2 on 1 high/low stretch isolation with the flat route in front and the curl route behind him:

The numbers advantage the all curl concept is afforded vs cover 3 is the same reason Manziel preferred it as his go to audible against Aggie defensive coordinator Mark Snyder’s Tampa 2 coverage. Made famous by Tony Dungy during his time with the Buccaneers, Tampa 2 is similar to cover 2, but remedies the obvious weak spot of cover 2 by having the Mike act as the “pole runner” and cover the deep middle third of the field. The Mike is essentially the insurance policy of cover 2 against the post route, and in theory affords the defense the luxury of getting the best of both the single high and two high coverage worlds. A bracket is formed over the #1 receiver with the corner and the safety, while the void between the safeties is secured with the Mike.

However, with the Mike bailing to get to his deep third responsibility, this results in a very similar coverage distribution to cover 3, as 4 defenders are now left to account for the underneath zones. This is why Manziel referred to the middle hook as “replacing” the Mike linebacker that is gone, and explained that he is given the freedom between the hashes to work and get open. The high low Manziel mentioned when introducing the play is the stretch placed on the flat defender with the curl and the flat route. In Tampa 2, this player is the cornerback, who is coached to take the first man to the flat.

In the clip below, A&M runs the all-curl play against Auburn in Tampa 2. Manziel probably could have thrown the middle curl for a completion with the Mike bailing, but ends up throwing the curl to the boundary. The weakside linebacker stays in the hook area eyeing the running back, which prevents him from getting into the curl window. Mike Evans is able to settle in the open void between the corner underneath and the safety over the top, then uses his size to body up the safety and secure the catch:

Without access to the A&M playbook from this time period, I am not sure how Manziel was taught which curl/flat side to work to if he didn’t like the middle hook. In the case of this particular play, he was flushed from the pocket and got the ball to his best playmaker. As mentioned earlier, some coaches will teach to work to the side of the hook defender that squeezes the middle. Others will teach the quarterback to work the boundary curl/flat vs 1 high and the field curl/flat vs 2 high because of the inherent numbers advantage each coverage structure presents. There is also the simple method of deciding pre-snap which side to work to based on where the qb sees the most grass or likes his best matchup.

The reason the all curl concept works so well against Tampa 2 is the same reason it doesn’t work so well against cover 2-numbers. With cover 2, the numbers advantage is now negated with the defense allotting 5 underneath defenders to match the 5 underneath receivers. The Mike can play the hook area, which allows the outside linebacker to rob #1 underneath once he sees #2 out to the flat. This is why cover 2 is generally considered one of the best coverages for shutting down short, lateral read pass route combinations. The obvious response for the offense in the continuing chess match would be to attack cover 2 at its weak point with a route in the middle of the field. The development of this kind of geometric passing game theory, where ideas about attacking defenses through the air in terms of precise spacing and numbers, is often credited to Bill Walsh and his West Coast offense. However, the man arguably most responsible for spawning the sophisticated passing attacks that have become ubiquitous across all levels of modern football is Sid Gillman, or as author Josh Katzowitz describes him, “The most important person in football that hardly anybody remembers.”

Despite being the only coach inducted into both the College football and Pro Football Hall of Fame, Gillman is largely unknown to the modern fan, primarily because he never won a Super Bowl. However, the impact he had on the evolution of offensive football is difficult to overstate. As Ron Jaworksi (who played for Gillman with the Eagles from 1979-81) explains in his book The Games that Changed the Game:

If there were a Mount Rushmore for pioneering football geniuses, Sid Gillman’s likeness would be on it. Sid, quite simply, is the father of the modern passing game. Every passing guru-from Al Davis and Don Coryell to Bill Walsh and Mike Holmgren-owes him a debt of gratitude. Every fan who loves “the bomb” should be grateful to Gillman. I know I was. For two years, I was the lucky recipient of Sid’s incredible knowledge, and I’d equate my experience with him to be the same as a physics student getting daily one-on-one tutoring with Albert Einstein.

Gillman’s coaching career began in an era when football orthodoxy overwhelmingly viewed pass-first coaches as a pariah. As Darrell Royal famously said in 1963, “Three things can happen when you pass, and two of them are bad.” However Gillman, who was inspired during his playing days by his pass-happy coach Frank Shmidt, was one of the first coaches who openly advocated using the pass to set up the run. The foundation of Gillman’s offensive approach was centered around one simple concept-get more people to an area of the field faster than your opponent. Extrapolating from that philosophy, he fine tuned his passing game all the way down to the granular level, evolving his aerial attack into an exact science that attacked defenses with surgical precision.

After spending 2 decades coaching at the college level and then a 5 year stint with the Los Angeles Rams, Gillman joined the AFL’s Los Angeles Chargers in 1960 as the head coach. The AFL knew it needed to present an exciting brand of football to have any hopes of competing with the NFL. Coupled with the fact that AFL ball was thinner and easier to throw, along with his offensive personnel being superior to the mostly watered down talent across the league, the AFL became the perfect match for Gillman’s pass centric philosophy. The most innovative idea Gillman had about the passing game was that it could be viewed and enhanced through the lens of geometry. In 1963, he sent assistant Tom Bass to meet with a mathematics professor from San Diego State to help break down their passing game and determine the most efficient methods of stretching defenses vertically and horizontally. As Josh Katzowitz notes in his book Sid Gillman: Father of the Passing Game, “If, as Pythagoras is credited as saying, ‘Numbers rule the Universe,’ why couldn’t math prove Gillman’s offense?”

What the professor and Bass eventually concluded was that triangles (more specifically, the pythagorean theorem) were of the utmost importance when designing an efficient passing system. The first leg of the triangle was the initial route stem the receiver takes up to the breakpoint, the second leg was the path he takes from the breakpoint to the spot the ball was caught, and the third leg was from that spot to the quarterback’s launch point on the throw. Gillman applied this theory as the foundational idea of his passing game and meticulously calculated receiver splits and quarterback drop depths so that no matter where they were on the field, the distance and amount of time the ball would be in the air for a specific pattern would remain the same. Essentially, he always wanted to make sure that the third leg of the triangle (the throw) for each route was uniform. The result was a carefully calibrated passing game predicated on exact timing and rhythm between quarterbacks and receivers-elements that are now universal in today’s offenses.

Gillman also used this mathematical approach to create a concept he referred to as “field balance theory”, which proposed that the offense could most effectively stretch the defense horizontally by placing a potential receiver in each area of the field. From Gillman’s 1981 Eagles playbook:

In order to put this theory into practice, Gillman’s innovative tactics included splitting his wide receivers out past the numbers and often releasing all five eligibles out into the pass pattern. He also placed a strong emphasis on using a pass catching tight end that could control the middle of the field in the hash area with seam routes. Gillman was one of the first coaches to begin utilizing the tight end as a two pronged weapon, a tactic that was eventually main streamed by Don Coryell, who was heavily influenced by Gillman. His motto of stretching the defense to its limit is perfectly illustrated by his version of the all-curl concept, a pattern his numbering system designated as “444”:

Gillman was notorious for his scrupulous attention to detail. For example, his coaching points just for this one play are laid out below:

“B.L.S to Buzz System” are written at the top as the quarterback reads, both of which are revolutionary concepts pioneered by Gillman and still used by quarterbacks today. “B.L.S” stands for best located safety, and is a principle that instructs the quarterback to identify both safeties and throw the ball to the receiver that is located the furthest away from them:

Once the quarterback identifies the best located safety, the “Buzz System” tells him to decipher how the defense is covering the previously discussed areas of the field to the read side:

On his quarterback alerts page for the all curl pattern, he lays out his adjustments for cover 2, which show the outside receivers running a burst release (slipping inside the cloud corner before readjusting to get back vertical) and sending the tight end down the middle of the field to exploit the void between the safeties. Alert #4 highlights the importance of the quarterback being aware of the danger players of a 1 high coverage structure, which are the 2nd underneath defenders (inside linebackers) that could drop into the curl window. He notes that “WR will handle 1st man!”, meaning that the outside wide receivers will adjust their path back to the quarterback to find the open window away from the first underneath player, which is the curl/flat defender. Beneath the diagrams, in a manner more obsessively detailed than what one could find in practically any other offensive playbook, Gillman lays out his preferred coverages to run this play against. Cover 6, which was Gillman’s verbiage for what is commonly known as cover 3, is first on the list:

In contemporary football, practically every team has some version of this concept in their playbook thanks in large part to Gillman’s influence. His disciples include Al Davis, who brought a vertical emphasis of Gilman’s passing game to Oakland and taught it to his young assistant Bill Walsh. Walsh would go on to incorporate many of Gillman’s principles into his own West Coast system that began to spread across the league in the 80s and 90s. At the college level, Doug Scovil and Lavell Edwards used a simplified version of Gillman’s offense with great success at BYU, which was later adopted and molded into the air raid system by Hal Mumme and Mike Leach. Vince Lombardi, John Madden, Chuck Knoll, and a host of other legendary coaches were all heavily impacted by Gillman’s innovative teachings. Today’s fans may not know who Sid Gillman is, but the fingerprints of the man affectionately known as the “Father of the Passing Game” are all over the modern game.